The Temple of Heaven and Wangfujing

I met up with Kevin bright and early Saturday morning, and we hopped on the now-familiar subway to Qianmen Zhan, a station right in the very heart of downtown Beijing, within walking distance of some of the city’s most exciting cultural and historical sites. After making our way through a tangle of alleyway markets (picking up, in the process, presents for my sister and mom, a gross iced tea, a yummy iced tea, some orange juice, and a little ceramic pot of yogurt which I drank with a straw) we finally found ourselves drawing close to our destination: Tian Tan, the Temple of Heaven. We strolled into a newly constructed, four-story mall-like complex half filled with vendor stalls, half empty space, but all mercifully air-conditioned (sadly, our real motivation in entering the building to begin with).

I acquired a cute green Adidas backpack to hold my purchases (one of which, Bean I bet you can guess which one this was,

and Mom, I can’t wait to give it to you, was rather heavy) and had a nice chat with the vendor. Kevin and I emerged once more into the blazingly white sun again and found a small stall at the side of the road selling baozi, steamed white buns filled with nearly every filling you could imagine (Kevin’s had meat in them, mine featured green beans and bai cai or white cabbage). We carried our bag of piping-hot baozi back into the mall complex, found a not-too-dirty spot on the stairs that was still relatively air-conditioned, and happily munched our lunch as we chatted about the temple we were about to visit.

and Mom, I can’t wait to give it to you, was rather heavy) and had a nice chat with the vendor. Kevin and I emerged once more into the blazingly white sun again and found a small stall at the side of the road selling baozi, steamed white buns filled with nearly every filling you could imagine (Kevin’s had meat in them, mine featured green beans and bai cai or white cabbage). We carried our bag of piping-hot baozi back into the mall complex, found a not-too-dirty spot on the stairs that was still relatively air-conditioned, and happily munched our lunch as we chatted about the temple we were about to visit.The Temple of Heaven, or Tian Tan, was first built in 1420, and saw many important developments and additions during the Ming and Qing dynasties. Tian Tan was where the ancient emperors used to come to pray to the gods for good harvests and b

umper crops, through an elaborate ceremony of dressing, chanting, fasting, meditating, and preparing sacrifices to placate the gods. The shape of the park is unique and symbolic of this place's special role as a place where the holiest person in China (the emperor) came to commune with the gods and beg for abundance for his people. The northern wall is semi-circular, while the southern half of the park is rectangular, a pattern symbolic of the ancient belief that heaven is round and the earth square. As the emperor made his way from the southern part of the temple grounds to the northern extreme, he moved from the earthy realm of his people to become closer to the divinity whose aid he was trying to enlist. (Kevin and I did this exactly backwards, by the way, being the lao wai that we are, moving from north to south... oops).

umper crops, through an elaborate ceremony of dressing, chanting, fasting, meditating, and preparing sacrifices to placate the gods. The shape of the park is unique and symbolic of this place's special role as a place where the holiest person in China (the emperor) came to commune with the gods and beg for abundance for his people. The northern wall is semi-circular, while the southern half of the park is rectangular, a pattern symbolic of the ancient belief that heaven is round and the earth square. As the emperor made his way from the southern part of the temple grounds to the northern extreme, he moved from the earthy realm of his people to become closer to the divinity whose aid he was trying to enlist. (Kevin and I did this exactly backwards, by the way, being the lao wai that we are, moving from north to south... oops).The buildings of Tian Tan are arranged along this

north-south axis, with a large circular marble terrace in the south used to worship heaven at the winter solstice, linked with the northern temple used to pray in spring for a bountiful harvest by a 360-meter-long raised walk called the Danbi Bridge. The two altars and the bridge altogether compose an axis of more than 1200 meters long, flanked on either side by centuries-old cypress trees, formal walks, and other sacred buildings. For instance, to the inner south of the west celestial gate is the Fasting Palace, where feudal emperors observed abstention before their rituals of worship and prayer, while the western part of the outer temple is home to the Divine Music Administration, which we didn't see because it cost extra money to go in, but which apparently was used to teach and perform the ritual music accompanying the divine ceremonies.

north-south axis, with a large circular marble terrace in the south used to worship heaven at the winter solstice, linked with the northern temple used to pray in spring for a bountiful harvest by a 360-meter-long raised walk called the Danbi Bridge. The two altars and the bridge altogether compose an axis of more than 1200 meters long, flanked on either side by centuries-old cypress trees, formal walks, and other sacred buildings. For instance, to the inner south of the west celestial gate is the Fasting Palace, where feudal emperors observed abstention before their rituals of worship and prayer, while the western part of the outer temple is home to the Divine Music Administration, which we didn't see because it cost extra money to go in, but which apparently was used to teach and perform the ritual music accompanying the divine ceremonies.Inside the northern temple itself, the sign at the entrance informed us, are such buildings as the Hall of Prayer for Good Harvests, the Hall of the Heavenly Emperor, the Imperial Vault of Heaven, the Beamless Hall, the Long Corridor, the Echo Wall, the Three Echo Stones, the Seven Star Stone and Nine-Dragon Juniper. It was truly a magical place. After an ice pop and the fourth iced-tea of the day (if I have any teeth left in my head by the end of this sugar-filled summer, it’s going to be a miracle), we finished up our tour of the park and temple grounds. Sadly, the Echo Wall was unavailable to visitors due to repairs, and Kevin and I wound up not quite being able to find the Fasting Palace, but besides these two, we saw nearly everything there was to see in the incredibly expansive grounds.

After all this walking, talking, and absorption of cultural and historical information, Kevin and I were about as wiped out as it is possible for two people to be. We dragged ourselves out the Western Gate and perched on a small, broilingly hot bit of concrete to plan the rest of our day. All I really wanted at this point in the day, I told Kevin plainly, was (1) to sit down, (2) to be cooled off. A taxi ride seemed the best way to provide both air conditioning and a softer, cooler place to sit than a hot, scratchy concrete slab, but this did not really solve the problem of where we ought to take the taxi to. We finally resolved to head to Wangfujing, one of the most popular spots in the city today, and gratefully climbed into the cool, cigarette-smelling interior of a nearby taxi

Arriving at Wangfujing was like stepping into another universe, leaving behind the Beijing I've come to kn

ow and entering a wealthy, ultra-advanced, fully cosmopolitan city center. We meandered through a breathtakingly gorgeous hotel, stopped to use their (Western style!!) bathrooms (for me, this involved a mini-bath by the sink as I unsuccessfully attempted to remove a few layers of salt and dust from my person), and wandered about the premises gaping at the luxury that is so frequently nowhere to be found in China. I smiled graciously at the concierge and other uniformed hotel attendants, trying to look like I belonged there (“you’ve got instant authority,” Kevin informed me bluntly, “you’re white.”) despite my dusty legs, sweaty arms, and the damp backpack clinging to the back of my shirt. We found our way to a giant underground mall (Oriental Mall -- it has an above-ground element as well) filled with the kind of brands and goods that Chinese marketplaces provide cheap imitations of – Rolex, Burberry, Tiffany’s, Armani Exchange, the list goes on and on and on – and I suddenly became aware that, in addition to wanting to sit down again and be cooled off, I was powerfully hungry.

ow and entering a wealthy, ultra-advanced, fully cosmopolitan city center. We meandered through a breathtakingly gorgeous hotel, stopped to use their (Western style!!) bathrooms (for me, this involved a mini-bath by the sink as I unsuccessfully attempted to remove a few layers of salt and dust from my person), and wandered about the premises gaping at the luxury that is so frequently nowhere to be found in China. I smiled graciously at the concierge and other uniformed hotel attendants, trying to look like I belonged there (“you’ve got instant authority,” Kevin informed me bluntly, “you’re white.”) despite my dusty legs, sweaty arms, and the damp backpack clinging to the back of my shirt. We found our way to a giant underground mall (Oriental Mall -- it has an above-ground element as well) filled with the kind of brands and goods that Chinese marketplaces provide cheap imitations of – Rolex, Burberry, Tiffany’s, Armani Exchange, the list goes on and on and on – and I suddenly became aware that, in addition to wanting to sit down again and be cooled off, I was powerfully hungry.After a bunch of befuddled wandering and consultation of some truly useless mall directories,

we found the food area of the mall at last, and ordered a pair of ginormous, piping-hot bowls of ramen noodles at a Japanese place called Mian Ai Mian (which means something like “Face loves noodles” or “Noodles love face” or “Noodles love noodles” – it’s unclear as “mian” means a number of different things), where I proceeded to demolish the entire bowl, soup and all, before helping Kevin a bit with his dessert of strawberry ice cream decorated with tapioca balls and (inexplicably) cornflakes. [See picture for proof of this feat – note Kevin’s not-emptied bowl in the background.]

we found the food area of the mall at last, and ordered a pair of ginormous, piping-hot bowls of ramen noodles at a Japanese place called Mian Ai Mian (which means something like “Face loves noodles” or “Noodles love face” or “Noodles love noodles” – it’s unclear as “mian” means a number of different things), where I proceeded to demolish the entire bowl, soup and all, before helping Kevin a bit with his dessert of strawberry ice cream decorated with tapioca balls and (inexplicably) cornflakes. [See picture for proof of this feat – note Kevin’s not-emptied bowl in the background.]More than a little full after all that ramen, but feeling refreshed and ready for new adventures, we made our way back to the surface and emerged into Wangfujing. Created to lead to a well drilled near the Yuan Dynasty Prince's Mansion nearly 700 years ago, the street of Wangfujing is now one of China's most popular shopping districts. Legend has it that an emperor during the Ming Dynasty wanted all of his 10 brothers to

build their mansions along this street in order to make it easy for him to keep an eye on them and make sure they didn't amass too much political power. The street was therefore christened "Shi wang fu" (Ten Princes' Mansions), merged with the old purpose of the street to the current-day name of "Wang fu jing" ("jing" means well). Kev and I actually saw the well, which has been symbolically restored and has a little fence around it off one of the small alleyways. Kevin and I sampled some of the local delicacies (him: sugared grapes on a stick, me: coconut juice straight out of the coconut) and steered clear of some of the others (scorpions, seahorses, pupae, crickets, and whole baby birds on a stick, to give just a few examples) as we strolled about taking in the sights and marvelling at the almost surreal cleanliness of the alleyway marketplace, so different from more authentic shopping opportunities in the dirty alleys of the rest of Beijing.

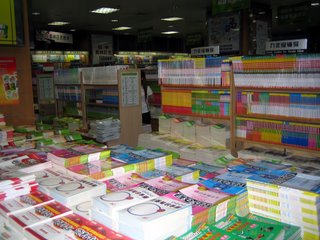

build their mansions along this street in order to make it easy for him to keep an eye on them and make sure they didn't amass too much political power. The street was therefore christened "Shi wang fu" (Ten Princes' Mansions), merged with the old purpose of the street to the current-day name of "Wang fu jing" ("jing" means well). Kev and I actually saw the well, which has been symbolically restored and has a little fence around it off one of the small alleyways. Kevin and I sampled some of the local delicacies (him: sugared grapes on a stick, me: coconut juice straight out of the coconut) and steered clear of some of the others (scorpions, seahorses, pupae, crickets, and whole baby birds on a stick, to give just a few examples) as we strolled about taking in the sights and marvelling at the almost surreal cleanliness of the alleyway marketplace, so different from more authentic shopping opportunities in the dirty alleys of the rest of Beijing.On our way back up the street, we made a stop at the Xinhua Book Store, which is apparently the

biggest bookstore in all of China. During our first trip past, I had refrained from entering, knowing that I would probably wind up spending the rest of the evening in the store and didn’t want to take Kevin away from his sight-seeing, but as he wanted to go in on our way back, I was certainly not going to complain. Kevin bought The Art of War and The Communist Manifesto, and I purchased Tao Te Ching (The Book of Changes), The Analects, The Life and Wisdom of Confucius, Tracing the Roots of Chinese Characters: 500 Cases, and an amazing book published by Yale University Press, but mercifully not as expensive as all the other imported books they had for sale (I purchased only Chinese books, as the English ones were all still American/European prices), called Key Concepts in Chinese Philosophy. Although this shopping spree compromises one of my larger purchases in China (and yes, it does figure that it was in a bookstore... is anyone surprised?

biggest bookstore in all of China. During our first trip past, I had refrained from entering, knowing that I would probably wind up spending the rest of the evening in the store and didn’t want to take Kevin away from his sight-seeing, but as he wanted to go in on our way back, I was certainly not going to complain. Kevin bought The Art of War and The Communist Manifesto, and I purchased Tao Te Ching (The Book of Changes), The Analects, The Life and Wisdom of Confucius, Tracing the Roots of Chinese Characters: 500 Cases, and an amazing book published by Yale University Press, but mercifully not as expensive as all the other imported books they had for sale (I purchased only Chinese books, as the English ones were all still American/European prices), called Key Concepts in Chinese Philosophy. Although this shopping spree compromises one of my larger purchases in China (and yes, it does figure that it was in a bookstore... is anyone surprised? anyone? anyone? Bueller...?), all together these books cost less than $20 USD. Simply unbelievable.

anyone? anyone? Bueller...?), all together these books cost less than $20 USD. Simply unbelievable.It was also in Wangfujing that I experienced two of my Chinese "firsts," each of which says loads about the current status of (and flaws in) Chinese society today, because they are "firsts" here but perfectly common occurances back home: I saw the first pregnant woman ever, in all my weeks in China, and caught sight of the first wheelchair-bound Chinese person. Each of these bears very interestingly on a different aspect of China's societal and governmental policies, and both are linked to the omnipresent, all-pervasive population problem, but I won't get too into it here for, erm, fairly obvious reasons, which might or might not have to do with internet censorship. That's all I'm sayin.

<< Home