HBA Teachers: A Brief Introduction

I'm planning to make this post a bit longer eventually... right now I've only got the head honchos covered here, but I'd eventually also like to introduce you to our

xiao ban ke and

dang ban ke teachers. Not sure how possible this is, given how very many teachers we have, but, hey, I can dream. :)

Feng LaoshiFeng Laoshi is the head of HBA, benevolent father figure with a reputation for almost fanatical enforcement of rules (most notably our Language Pledge, which forbids students from using any language other than Chinese except in dire emergency situations and when speaking to family back home -- and even then, only out of earshot of other students).

Yan LaoshiYan Laoshi is like a friendly little panda bear who just wants to hug you and love you and teach you lots and lots of good Chinese. Her kind manner and chirpy voice belie a formidable intellect and a fierce strictness -- students lucky enough to find themselves under her tutelage are almost incessantly corrected in their grammar, pronunciation, phrasing, and so on, but mind far

less than they normally would. If you ask Yan Laoshi to explain a grammar point to you, you will not only receive a thoughtfuland precise answer but will find yourself tested on it -- probably in sentences involving recently-studied grammar patterns and this lesson's new vocab words -- several times in a row, gently corrected until you've got it perfectly down.

Wang LaoshiWhile Yan Laoshi rules her Chinese classroom on charm and perkiness, Wang Laoshi rules with the old "iron fist in the velvet glove." As I've never had the occasion to observe anything less than perfect classroom behavior from anyone at HBA (literally, never, it's a little creepy what good little boys and girls we are), I don't know how (or if) Yan Laoshi would cope with problems in the classroom. I have no such reservation about Wang Laoshi -- in her classroom, she is the law. A tall woman, whose lazy eye and mild duck-footedness somehow do not detract from her stateliness, Wang Laoshi is apparently the only teacher not deathly afraid of Feng Laoshi, and apparently calls him by his first name and tells him he's talking rubbish if she thinks he is. I would imagine that Wang Laoshi is a bit like the Chinese version of the Unsinkable Molly Brown,

with a great stentorian voice and a jovial, if autocratic manner. She is, as my mom would say, "a big softy" on the inside, who cares deeply about her students and their well-being as well as their Chinese skill. Still, I would not want to cross Wang Laoshi.

Tian LaoshiTian Laoshi is the only male da ban ke teacher, and lags somewhat behind the other two in terms of teaching method, ability to explain tricky concepts, and overall style. I don't blame him, of course -- he's the newcomer, and the other two teachers weren't born with those skills, so he's got time. His pronunciation is less than clear a good deal of the time, which is a pretty big

flaw in a foreign language teacher, particularly one teaching Chinese, as writing the character on the board for us does nothing if we don't know how to say it properly. During dictation this is also a pretty big drawback. However, he's quite good at explaining things, most notably one-on-one, as his classes are invariably about three times more boring than the others' classes, and sometimes begin to drag. However, he's a good guy -- I think he's on his way.

Beijing Planning Exhibition Hall

So on Wednesday we went to the Beijing Planning Exhibition Hall, which is an enormous complex filled from top to bottom with exhibits of Beijing's architecture and city planning for all its various districts. The coolest part of the museum was probably the eastern section of the third and fourth floors, which features a huge aerial photograph 10 times as big as the average Beijing apartment. The photograph is printed on nearly a thousand lit glass floor panels and features a middle section with many districts of the city built in tiny scale models complete with flickering lights and color-coded sections. There is a picture of it below -- truly very cool. More information about this exhibit in particular can be found

here.

The entire first and second floors of the museum, however, were entirely devoted to exhibits concerning the coming Olympics -- plans for sculpture and architectural

planning were everywhere. All this Olympic stuff got me thinking about the adorable

mascots China has designed for the 2008 Games. Although not prominently featured in the Exhibition Hall, these little guys (

Fuwa) are simply everywhere you go in the city -- people are selling them as keychains, posters are on the sides of buildings and athletic centers, taxi drivers have them as little figurines dangling from the winshield or perched precariously on the dashboard.

So much media exposure (besides having the desired effect of me thinking that the mascots are cool,

that Beijing has got its act together for the Olympics, and that it would be sort of cool to come back here in 2008 to watch the Games) go me thinking, for no reason whatsoever, which of the mascots reminds me of which of my family members. Well, okay, it's not no reason whatsoever -- big motivating reason number one is that I miss my family and think about them a lot, and minor auxiliary reason number two is that Yingying

really reminds me of my dad, and Nini sort of reminds me of my sister.

Anyway, the

link above has more information about these five cute little guys than you would probably ever want to know, so I can spare you all the details, but it's really kind of amazing how well-thought out the whole "Olympic Mascot" thing is for Beijing. They manage to incorporate not only the colors of the five Olympic rings (blue, black, red, yellow, green); five different symbols of Chinese culture/the Olympic games (fish, panda, Olympic torch, antelope, Chinese kite); five different blessings (prosperity, happiness, passion, health, and luck); five different regions' cultural art forms; they also have a message hidden in the cute di-syllabic names typical of Chinese children (Beibei, Jingjing, Huanhuan, Yingying, and Nini come together to form the phrase

Bei jing huan ying ni, or "Beijing welcomes you"), and, given their familial relationship,

also typify the importance of family in Chinese culture.

Have I left things out? Oh, yes, there is even more -- I haven't gone into the characters of their names, which have more to do with their blessings than with their relation to the welcoming message, since the characters of Beibei are not the

bei of Beijing (Beibei's name contains two characters developed from the ancient pictograph of a cowrie shell, which used to be used for currency in ancient times and is now found in many Chinese characters having to do with money, whereas the

bei of Beijing is drawn quite differently and means "north" or "northern," and so on), nor into their particular characters: who is the oldest and youngest among them, what their personalities are like, and which Olympic sports they do best. It's really nothing short of astounding. But I digress. Widely. As usual. :) But aren't they cute?

Tanzhe Si

Tanzhe Si (rather picturesquely translated as "

Tanzhe Si (rather picturesquely translated as "The Temple of the Pool and the Wild Mulberry

") is a typical Buddhist temple, located in the Tanzhe Hills on the western outskirts of Beijing, about a 1 or 2 hour drive by taxi from BCLU. Apparently, it was the first temple that appeared in the Beijing area, ever. When the temple was built during the Jin Dynasty (AD265- 420), Buddhism began to spread in the area southwest of present- day Beijing, later known as  Youzhou, giving rise to the a saying that "First there was the Tanzhe Temple, then there was Beijing."

Youzhou, giving rise to the a saying that "First there was the Tanzhe Temple, then there was Beijing."

According to this website, Buddhism was introduced into China during the Eastern Han Dynasty (AD 25-220). Temples were built throughout the country. The places where images of Buddha were enshrined and eminent monks from India stayed were regarded as sacred places like government offices. As the saying goes, "There were 480 temples during the Southern Dynasties. Many famous mountains were occupied by monks." Cast during the reign of Emperor Chenghua of the Ming Dynasty, the bell at the Tanzhe Temple is 0.47metre in height, 0.31 meter in rim diameter and 24.8 kilograms in weight. On the waist of the bell is an inscription of seal characters which means that the bell was made uring the reign of Chenghua of the Ming Dynasty. It is decorated with fret patterns and a design of two dragons laying with a pearl. The exquisite bell is a proof of the renovation and extension of the Tanzhe Temple to the present cale at the end of the 17th century.We were accompanied in our trip to the temple by the old, rich architect who gave us our tour of the construction areas on the first day of our trip. I made the mistake of asking him to explain his take on the Chinese architectural/design principle of feng shui, and so was treated all trip long to cries of "He Kaili! Lai, lai..." ("Kelly! Come here, I want to show you...."). He was a funny sort of man. He reminded me in a lot of ways of certain middle-aged, very self-satisfied men I've known in the US. He was fond of taking us all out for lunch and ordering far more food than the group could ever eat, of monopolizing conversation to share his wisdom and ideas, and of making sweeping pronouncements and jokes with the easy confidence of a rich man in a land where so many have so little.

the construction areas on the first day of our trip. I made the mistake of asking him to explain his take on the Chinese architectural/design principle of feng shui, and so was treated all trip long to cries of "He Kaili! Lai, lai..." ("Kelly! Come here, I want to show you...."). He was a funny sort of man. He reminded me in a lot of ways of certain middle-aged, very self-satisfied men I've known in the US. He was fond of taking us all out for lunch and ordering far more food than the group could ever eat, of monopolizing conversation to share his wisdom and ideas, and of making sweeping pronouncements and jokes with the easy confidence of a rich man in a land where so many have so little.

My second mistake of the  trip was wearing my cute new espadrilles, which were very cumbersome seeing as the second part of our trip involved crossing a stream bed (yes, by leaping from rock to rock -- I removed the shoes) and then hiking a rough trail to a more hidden temple area and some scenic outcroppings. The trail was beautiful, though... well worth the inconvenience. My third mistake was to ask my teachers a question about the process of prostrating yourself before Buddha. In a flurry of excitement they ushered me over to the temple's main monk, proud to have a student with a question. Embarrassed, I stumbled out my question before the man in maroon robes, who gave me an answer I couldn't understand while fingering his string of wooden beads and staring at the ceiling.

trip was wearing my cute new espadrilles, which were very cumbersome seeing as the second part of our trip involved crossing a stream bed (yes, by leaping from rock to rock -- I removed the shoes) and then hiking a rough trail to a more hidden temple area and some scenic outcroppings. The trail was beautiful, though... well worth the inconvenience. My third mistake was to ask my teachers a question about the process of prostrating yourself before Buddha. In a flurry of excitement they ushered me over to the temple's main monk, proud to have a student with a question. Embarrassed, I stumbled out my question before the man in maroon robes, who gave me an answer I couldn't understand while fingering his string of wooden beads and staring at the ceiling.

The teachers (and architect, who by this time seemed to think of himself as a  kind of personal mentor to me) explained the process, which was actually quite interesting -- my question regarded the reasoning behind the placement of the hands during the worshipping, which is apparently meant to symbolize offering your xin (heart and mind, all inner thoughts) to the Buddha, laying open your sould in reverence for him. "Now you try it, now you try it, Kaili," my teachers bubbled after I had suffered through this somewhat awkward exchange with the monk -- compounding an already sufficiently embarrassing situation. "Hao," I agreed, somewhat reluctantly, and, with the entire class looking on, performed the ceremony of prostrating myself three times with ritual hand gestures before Buddha. It was certainly interesting, though I think I might have preferred to do it without everyone else looking on.

kind of personal mentor to me) explained the process, which was actually quite interesting -- my question regarded the reasoning behind the placement of the hands during the worshipping, which is apparently meant to symbolize offering your xin (heart and mind, all inner thoughts) to the Buddha, laying open your sould in reverence for him. "Now you try it, now you try it, Kaili," my teachers bubbled after I had suffered through this somewhat awkward exchange with the monk -- compounding an already sufficiently embarrassing situation. "Hao," I agreed, somewhat reluctantly, and, with the entire class looking on, performed the ceremony of prostrating myself three times with ritual hand gestures before Buddha. It was certainly interesting, though I think I might have preferred to do it without everyone else looking on.

Grumbling aside, this really was a wonderful trip, and I think Tanzhe Si is probably one of my favorite places  I've been in China so far. The Lama Temple, while also beautiful, did not have the kind air of sacredness and timelessness that this place had. The hazy mountains in the distance, the serene Buddhist architecture, the careful placement of trees and stones in the courtyard full of worshippers, the quiet trails on the side of the mountain and the soft splashing of the brook outside the temple's eastern wall -- all combined to form what I learned was, for a number of reasons, incredible feng shui, which began with the naturally good energies of the location (with mountains shaped like a sleeping dragon to the north and a broad stretch of lazy river water to the south) and was carefully enhanced architecturally with respect for the feng shui of the underlying landscape. You could really imagine monks finding an inner peace at this temple, of sitting quietly as one with the air, water, and earth around them, and thinking up the deeply profound poetry of the Tao Te Ching (Dao De Jing).

I've been in China so far. The Lama Temple, while also beautiful, did not have the kind air of sacredness and timelessness that this place had. The hazy mountains in the distance, the serene Buddhist architecture, the careful placement of trees and stones in the courtyard full of worshippers, the quiet trails on the side of the mountain and the soft splashing of the brook outside the temple's eastern wall -- all combined to form what I learned was, for a number of reasons, incredible feng shui, which began with the naturally good energies of the location (with mountains shaped like a sleeping dragon to the north and a broad stretch of lazy river water to the south) and was carefully enhanced architecturally with respect for the feng shui of the underlying landscape. You could really imagine monks finding an inner peace at this temple, of sitting quietly as one with the air, water, and earth around them, and thinking up the deeply profound poetry of the Tao Te Ching (Dao De Jing).

In fact, I think I'll leave you with one of my favorite verses from the book, which I'm reading in my spare time (what spare time?). The first verse:

道可道,非常道。

名可名,非常名。

无名天地之始。

有名万物之母。

故常无欲以观其妙。

常有欲以观其徼。

此两者同出而异名,同谓之玄。

玄之又玄,众妙之门。

There are ways but the Way is uncharted; There are names but not nature in words: Nameless indeed is the source of creation But things have a mother and she has a name. The secret waits for the insight Of eyes unclouded by longing; Those who are bound by desire See only the outward container. These two come paired but distinct By their names. Of all things profound, Say that their pairing is deepest, The gate to the root of the world.(Trans. R. B. Blakney)

The Imperial College

Guo zi jian, or the "Imperial College," was ancient China's highest seat of learning, combining the functions of what would now be called the Ministry of Education with those of a National University. It was once a stage for the Emperor, who frequently came here to read Confucian classics to an audience of thousands, mostly

composed of civil and military officials from the imperial court and students of the Imperial College itself.  Students came here to study the Confucian classics in preparation for the imperial examinations. The college not only trained and educated the elite, but also received foreign students from numerous different countries promoting cross-cultural exchange. Those who tested best on the imperial examination were permitted to enroll in the College, and a special ceremony for the top scorers ensued. The main gate has not one, but three entrances: one for the second-place scorer, one for the third-place scorer, and the middle one, the largest, through which only the top scorer and the Emperor himself were allowed to pass. I'm not going to lie, it was kind of a thrill to walk through that archway...

Students came here to study the Confucian classics in preparation for the imperial examinations. The college not only trained and educated the elite, but also received foreign students from numerous different countries promoting cross-cultural exchange. Those who tested best on the imperial examination were permitted to enroll in the College, and a special ceremony for the top scorers ensued. The main gate has not one, but three entrances: one for the second-place scorer, one for the third-place scorer, and the middle one, the largest, through which only the top scorer and the Emperor himself were allowed to pass. I'm not going to lie, it was kind of a thrill to walk through that archway...

Anyway, some brief info on the life and times of this very picturesque cultural site: the Imperial College

was first established in 1287 during the Yuan Dynasty and subsequently enlarged several times, attaining its present dimensions during the reign of Emperor Qianlong of the Qing Dynasty. After the founding of the People's Republic in 1949, the Imperial College was completely renovated and the Capital Library was incorporated within its grounds.

Apparently, the east and west halls of the Bi yong Hall (picture above: the east hall, unless my memory fails me) originally housed the famous "Qianlong Stone Scriptures." In the middle of the 18th century, Emperor Qianlong ordered to have the Thirteen Classics engraved in stone. To carry out this order, Jiang Heng, a scholar from Jiangsu Province, spent 20 years carving the 630,000 Chinese characters onto 189 stone tablets. Today these tables are located to the east of the Taixue Gate, so we didn't get to see them, but we did get to see where they used to be kept, as well as many photographs of the engraved tablets.

Look! A picture with people in it! From left to right:

[Back row]: Ben Jiemin (Yalie, super friendly; real name: Ben); Feng Shi (also from Yale, also super friendly -- fifth year, and my "big sister" for my Zhong guo jia ting experience... she's awesome); Ai Jingquan (another Yalie, from Canada, pretty cool guy as well, Kevin and I hung out with him for most of the trip; real name: Cameron); me and Kev, obviously... He Kaili and Zhuo Kaiwei for the purposes of this trip; two third-year graduate students whose names I do not know; a fourth-year named Bridget who doesn't talk much but stands around looking haughty and sort of bored... although she did talk to us a little.

[Front row]: fourth-year Yalie, friends with Feng Shi and dating Hao Ping; Hao Ping himself (real name unknown); Xiao Kan (my buddy, also a Yalie, real name: Colin); Liao Laoshi (small, awesome teacher, who Cameron told me we ought to nominate for "world's cutest teacher" ... it's true, she's like this continually-smiling little bouncy ball who also happens to teach you Chinese); Xiao Fei (from Harvard I believe, real name uknown, pretty quiet but quite nice); and, last but not least, Feng Dao (yet another Yalie, also my pal, Japanese with a Korean girlfriend [I think... don't quote me on that] and a big interest in modern architecture).

Phew.

This is the view from the main classroom building (in which no photos were allowed), called the

Bi yong (Jade Disc) Hall. This square pavilion, standing in the center of a circular pond, has really lovely architecture, although I couldn't photograph it, featuring a double-eaved roof surmounted by a golden sphere on top. Outside, the pond is crossed by four marble bridges and provided on four sides with stone spouts in the shape of dragonheads. These bridges are strung from end to end with garlands of little red tasselled placards, which eager tourists and young college students from all over Beijing come to fill out with their wishes, hoping that placing their carefully penned hopes and schemes in this most auspicious of Chinese learning centers will make their dreams for the future come true.

Hutongs

Beijing's "hutongs" are lanes or alleys formed by lines of si he yuan (a compound with houses around a courtyard). The word "hutong" apparently originates from the Mongolian word "hottog" which means "well," referring to the fact that many hutongs were formed when villagers would dig out a well a ways off from their neigbors and would settle around the area there. Today, the word hutong refers to these ancient lanes and alleys

where Beijing residents still live. Nearly all of Beijing's Hutongs are laid out in either east-west or north-south directions, although the clusters of buildings have developed so much over the centuries that there is not much order to be found in them today.

This is what my "Social Study Week" packet, distributed to us last Sunday, has to say about hutongs:

"How many hutongs are there in Beijing? Old local residents have a saying: "There are 360 large hutongs and as many small hutongs as there are hairs on an ox." Laid out in a chessboard pattern which was established as early as the Ming Dynasty, these hutongs cross-cut the city into tiny squares.

In those days the capital was divided into the eastern, western, northern, southern and central districts, with a total of 33 neighborhoods, divided again into hutongs. In the Tang Dynasty, the city, then named Youzhou, was divided into 28 walled residential districts guarded by sentries. A curfew was enforced at night. Youzhou was renamed Xijunfu in the Liao Dynasty and the city was divided into 26 residential districts. In the Jin Dynasty it became Zhongdu (the Central Capital) and was divided again into 60 residential areas. Under the Yuan, the city was renamed Dadu (Great Capital) and divided into 50 districts, including Jintaifang (Golden Terrace District) and Wendefang (Literature and Morality District). The 33 neighborhoods mentioned above were established under the Ming emperors Hongwu (reigned 1368-1398) and Jianwen (reigned 1399-1402). The figure increased to 40 after the time of Emperor Yongle (reigned1403-1424). The Qing rulers made use of the

In those days the capital was divided into the eastern, western, northern, southern and central districts, with a total of 33 neighborhoods, divided again into hutongs. In the Tang Dynasty, the city, then named Youzhou, was divided into 28 walled residential districts guarded by sentries. A curfew was enforced at night. Youzhou was renamed Xijunfu in the Liao Dynasty and the city was divided into 26 residential districts. In the Jin Dynasty it became Zhongdu (the Central Capital) and was divided again into 60 residential areas. Under the Yuan, the city was renamed Dadu (Great Capital) and divided into 50 districts, including Jintaifang (Golden Terrace District) and Wendefang (Literature and Morality District). The 33 neighborhoods mentioned above were established under the Ming emperors Hongwu (reigned 1368-1398) and Jianwen (reigned 1399-1402). The figure increased to 40 after the time of Emperor Yongle (reigned1403-1424). The Qing rulers made use of the existing city structure and divided the capital into five districts, reducing the number of residential districts to 10.During the last years of Dynasty, the old residential district system was abolished and Beijing divided into 10 outer districts and 12 inner districts. The city is now divided into four districts -- East City, West City, Chongwen and Xuanwu -- each of these comprised of numerous sub districts.

existing city structure and divided the capital into five districts, reducing the number of residential districts to 10.During the last years of Dynasty, the old residential district system was abolished and Beijing divided into 10 outer districts and 12 inner districts. The city is now divided into four districts -- East City, West City, Chongwen and Xuanwu -- each of these comprised of numerous sub districts.

At present, there are about 4,550 hutongs, the broadest over four meters wide and the smallest -- the eastern part of Dongfu'an Hutong, a mere 70 cm across -- just wide enough for a single person to traverse. Although the city has changed a great deal over the last 500 years, the hutongs remain much the same as during Ming and Qing times."

the last 500 years, the hutongs remain much the same as during Ming and Qing times."

Our trip through the hutongs of Beijing's Houhai area was simply lovely -- beautiful scenery, fascinating architecture, and, of course, wonderful company (Kevin came with us :). It was a long and somewhat tiring day (by about 4pm, the three-wheeled carriages looked mighty tempting), but definitely one of my favorite things I've done so far in Beijing. This post is short on anecdote and long on pictures and history, but that's mostly what the day involved: immersion in and experience with the living history of the capital city.

The Prince's Palace

Part two of our trip to the Hutongs was an afternoon in the beautiful gardens of an ancient imperial palace. Prince Gong's Palace is the most completely preserved royal residence in existence in China today

, and consists of the Mansion and the "Garden of Splendor" (also called

Cui jin), which, according to the sign which greeted us by the entrance, "implies that it is a collection of unsurpassed beauty and charm." It was certainly charming -- tranquil and beautiful, nestled in the heart of Beijing's most historic hutong district (on the eastern shore of

Shi cha hai, one of Beijing's most beautiful lakes, and near

Hou hai, the nightlife spot I went to with Sara earlier in my trip). The middle section of the Garden centers around the "Fu Stele," on

which the Chinese character "

fu" (happiness) is inscribed, personally handwritten by Qing Emperor Kangxi in the 1600s. Visitors are invited to

mo (stroke) the surface of the character to bring luck, rather like people rubbing John Harvard's foot when they come to

Harvard Yard. (Kevin and I both did it -- see the picture of Kev at the left).

The rear section of the garden has a multi-leveled artificial hill built of Lake Tai stones. The bottom level has tunnels running through it and contains the "Fu Stele" I mentioned above. On the second level of the garden are two pools where lotuses were blooming and a small wooden boat floating on the pond's placid surface. The eastern courtyard of the garden is surrounded by a low wall and contained all manner of different

flowers and trees. Screened by the Garden's large man-made hill is the "Hall of Happiness," which was apparently built in such a way that sunlight falls on it from dawn to dusk --said to be the only building of its kind in Beijing at the present time. According to recent research by literary scholars, it was at this Mansion that Cao Xueqin, author of

Hong Lou Meng (A Dream of Red Mansions), lived the life he went on to write about in his famous novel about the decline of Chinese feudal society. We stayed at the Prince's Palace for about two hours, before setting out once again for more Hutongs and some further investigation of Beijing's historic architecture.

The Lama Temple

Yonghe Gong

Yonghe Gong (The Lama Temple), built in 1694, is Beijing's largest and best known Buddhist lamasery. The Lama Temple is part of the Gelukpa ("Yellow Hat") Sect of Tibetan Buddhism, and was only able to survive China's Cultural Revolution through the protection of Chinese President Zhou

Enlai. The temple did well in pre-Community Beijing in part because the Manchu Qing emperors, though officially Confucians, were attracted to Lamanistic Buddhism. This is particularly interesting given the current political situation between China and Tibet.... but as usual, I'll try to steer clear of overt political commentary on this blog.

According to

this website, among the characteristic features of Tibetan Buddhism are its ready acceptance of the Buddhist Tantras as an integral and culminating part of the Buddhist way; its emphasis on the importance of the master - disciple relationship for both religious scholarship and meditation; its recognition of a huge pantheon of Buddhas, bodhisattvas, saints, demons, and deities; its sectarianism, which resulted less from religious disputes than from the great secular powers of the rival monastic organizations; and, finally, the marked piety of both monastic and lay Tibetan Buddhists, which receives expression in their spinning of prayer wheels, their pilgrimages to and

circumambulation of holy sites, prostrations and offerings, recitation of texts, and chanting of Mantras, especially the famous invocation to Avalokitesvara Om Mani Padme Hum, which I might have heard some people chanting while I was at the temple yesterday.

The main buildings of the Yonghe Gong are built along a central axis, proceeding from the Yonghe Gate Hall, through the Yonghe Gong Hall, Yongyou Hall, Falun Hall, and Wanfu Ge Hall, ending up with the Suicheng Lou Hall, which is home to a 20 foot statue of Tsongkhapa, the founder of the Gelukpa Sect. The area was simply lovely -- all photos were taken only outside, because photographs are forbidden inside the places of worship themselves -- and very peaceful, too. Amid the throngs of tourists wandering quietly through the temple were people who had actually come to worship: kow-towing before the giant Buddha statues (which, unlike the idols worshipped in some religions, are merely viewed as seats of divinity rather than divine in and of themselves), holding their sticks of incen

se high over their heads and prostrating themselves before the great religous symbols before us.

While the most dedicated Tibetan Buddhists (i.e., monks) seek nirvana, for the comThere are a number of Buddhist statues in every hall, which one of the other students, a Religion major back home in the states, was able to tell us a lot about. She informed us thatmon people, the religion often still retains shamanistic elements. Worship includes reciting prayers and intoning hymns, often to the sound of great horns and drums (though none of this was heard at the Lama Temple). A large pantheon of spirits, ghouls, and genii are often portrayed being crushed by Buddhas and bodhisattvas (future Buddhas) in sculpture, which we saw but I was of course unable to photograph. The monastic orders of this sect of Buddhism apparently include abbots, ordained religious mendicants, novices (candidates), and neophytes (children on probation). We caught sight of a monk near the last temple (see picture) and Kevin told me the story of why many Buddhist monks in China wear a garment which only covers one

arm, and why they use only one hand (rather than two, clasped in a prayer-like position) in making a bow.

The legend is this: many many years ago in ancient China, a young Buddhist worshipper named Shenguang desperately wanted to speak with Bodhidharma, the founder of the Chan sect of Buddhism in China (whose practices are known as Zen Buddhism in Japan), to join the master's monastery and spend the rest of his life seeking enlightenment.

This website tells the story thus:

"Shenguang pursued Bodhidharma all the way to Xiong Er Shan( Bear's Ear Mountain), which was in the Song range, the middle range of the five great mountain ranges of China. Bodhidharma was sitting there facing a wall, not speaking to anyone. Shenguang tried to talk to Bodhidharma, but the Patriarch completely ignored him.  And so Shenguang knelt there. He knelt for nine years while Bodhidharma sat. After nine years of kneeling his skill was fairly well developed, but it had not yet been brought to realization. In the winter of the ninth year of kneeling, there was a great snowfall. The snow covered him as he knelt there. It reached clear up to his waist. Probably he was shaking with cold and decided to try to speak to the Patriarch again. 'Patriarch, please be compassionate and transmit the Dharma to me. I realize now that you have Way virtue, that you are One Who Has Obtained the Way.'Bodhidharma asked him, 'What is falling outside?''Snow.''What color is the snow?''Snow is white.''When the snow turns red, I will transmit the Dharma to you.' This was a test. But by that

And so Shenguang knelt there. He knelt for nine years while Bodhidharma sat. After nine years of kneeling his skill was fairly well developed, but it had not yet been brought to realization. In the winter of the ninth year of kneeling, there was a great snowfall. The snow covered him as he knelt there. It reached clear up to his waist. Probably he was shaking with cold and decided to try to speak to the Patriarch again. 'Patriarch, please be compassionate and transmit the Dharma to me. I realize now that you have Way virtue, that you are One Who Has Obtained the Way.'Bodhidharma asked him, 'What is falling outside?''Snow.''What color is the snow?''Snow is white.''When the snow turns red, I will transmit the Dharma to you.' This was a test. But by that time Shenguang could figure out what to do.'Fine,' he thought, 'You want red snow?' And so he took his precept-knife, which was carried by the ancients. It was to use if a situation ever arose in which one would have to break a precept. Rather than break a precept, one would prefer to use the knife to cut off one's own head. But now Shenguang grabbed the knife and sliced off one of his arms. The blood spurted out all over the place and colored the snow red. He took up a bunch of the red snow and went before Bodhidharma, holding it aloft to offer to him. 'See, the snow is red,' he said.Bodhidharma was impressed by Shenguang's devotion to his study and accepted him as his student, making h

time Shenguang could figure out what to do.'Fine,' he thought, 'You want red snow?' And so he took his precept-knife, which was carried by the ancients. It was to use if a situation ever arose in which one would have to break a precept. Rather than break a precept, one would prefer to use the knife to cut off one's own head. But now Shenguang grabbed the knife and sliced off one of his arms. The blood spurted out all over the place and colored the snow red. He took up a bunch of the red snow and went before Bodhidharma, holding it aloft to offer to him. 'See, the snow is red,' he said.Bodhidharma was impressed by Shenguang's devotion to his study and accepted him as his student, making h im the Second Patriarch. And so the First Patriarch and the Second Patriarch continued the Buddha's teaching down through the ages."

im the Second Patriarch. And so the First Patriarch and the Second Patriarch continued the Buddha's teaching down through the ages."Now, not all Buddhist monks follow the practice of using a one-handed greeting and a one-armed robe -- typically only Shaolin monks do it this way, and I am not sure of the relation between Shaolin and Tibetan monastic practices, but the monk we saw (see picture) was certainly wearing Shaolin-looking dress. The atmosphere of the whole place was somehow holy, the air filled with incense and the silent prayers of the worshipers bowing before the great serene likenesses of their leader.

The Great Wall

Yes, folks, I finally went. The Great Wall of China, the sight I've been most longing to see over here... I finally made it! And what a trip it was...

Sara usually does the Great Wall with her

volunteers every time she gets a new batch in, and she promised to hold off on this group's trip until Kevin got to Beijing, so we could all go together. After a bright and early start, and a quick trip to pick up a few

dan bing f

ried pancake with egg(a kind of and scallions and lots of yummy sauce), I hailed a taxi, and, after an interesting ride in which my taxi driver stopped not once, not twice, but seven different times to ask directions (Sara's apartment is sort of out of the way) finally made it out to the Sixth Ring Road. After some hellos, especially to Sara's Chinese friend Yannan, whose English isn't the best but who was accompanying the rowdy group (of mostly 18-20-year-old boys) to the Great Wall as well, we all piled into the van for the hour-long drive to Shixiaguan, the relatively-newly-opened section of the Great Wall closest to Beijing, known for its strikingly steep ascent and the beautiful foliage that covers the mountainside around it.

It was a mistly day, and Sara, Kevin and I munched our

dan bing and chatted about the day's plans as the 9-person-van barreled along the highway, taking us from Sara's apartment in the suburbs of t

he Sixth Ring Road to the truer countryside, where homes and factories began to mingle with farms and grassy areas. The smell of animals and manure began wafting in through the windows and great green mountains began to loom ever closer in the whitish, misty air.

It was already quite hot when we reached the starting point -- a smallish parking lot filled with buses and cars and eager tourists, with the Great Wall winding its way up and over the moutains on either side. We purchased our tickets (mine, a half-price student ticket, also involved a sort of oral quiz from the lady selling me the ticket, which tested my Chinese more than proved my identity -- her: [suspicious scowl] "What year are you?" me: [confused] "Umm... here I am a second-year student -- second year Chinese student -- but in America I am fourth-year...?" Although I'm still not quite sure what she meant by the question, I must have passed, because without another word my ID was returned to me and a student-priced ticket was forked over shortly thereafter) and wandered over to the entrance.

The climb was simply beautiful -- there's really no other way to describ

e it. A word to the wise, however: anyone who thought that the Great Wall of China would be a nice stroll through the mountains on a nice raised walkway ought to be disabused of this pleasant notion as soon as possible. The Great Wall was constructed not as a kind of outer retaining wall against nicely settled areas, but to create a system of lookout posts and a means of transferring messages and information across great unsettled expanses of wilderness. According to some historians (although not the one who came to speak to us at the beginning of HBA), the Great Wall also served to create an elevated military roadway through the rugged terrain by speeding the deployment of soldiers from one area to another along the Wall. If that is true, I can only express my deepest sympathy for all those soldiers who needed to make treks like the one we experienced yesterday in full dress and carrying all their gear, because it was hard enough in light summer clothes and a backpack carrying little more than some water and my camera!!

Difficulty aside, however, the climb was amazing -- beautiful -- simply stunning. The section of the Wall we climbed has been restored, but although many of the stones are not original the layout and construction are mostly the same. Pausing (for breath!) at many of the watchtowers and guard platforms staggered up the slope, I loved to duck inside and just imagine all the men w

ho had made this spot their home, who had paused in this same area many hundreds or even thousands of years before I, too, had reached it. Did the sweet smell of the purple flowers growing up along the edge of the Wall inspire them, too? Could they see farther across the green mountains in the days before air pollution and busses of tourists? What about the men who had built the Wall, or the invaders it was meant to keep out. Was this section of the Wall ever breached? Just how many feet had trod upon the stones now so warm beneath my shoes?

I made a few friends on the way up, too -- a guy from Westchester named Mark, who was up in China on a weekend off from the documentary he was shooting in South Korea; a Chinese woman and her daughter, who wanted to take a picture with me (sometimes it seems to me that Chinese people are more interested in seeing and photographing the foreigners they encounter at tourist spots more than the sights themeselves), and a guy from the Philippines who spoke excellent English but still wanted the same thing as the Chinese woman, and managed a very backlit picture of the two of us in front of a fort window by snapping a shot on his camera phone. [Speaking of pictures, as always, all the shots in this entry were taken by my and are "clickable," meaning that you can see them bigger and more in detail by clicking on them -- and there are more pictures of the infinitely gorgeous Wall and its scenery on my actual website

here.]

We all reconvened at the top of the wall and took some pictures (including an all-China Care one,

which Yannan and I exempted ourselves from), and began the long and sweaty trek back down the wall on wobbly legs, dreaming of showers and passing around bottles of water. After we all got safely down again, we hung out for a while beside a garden at this section of the wall's lower extremity, then enjoyed the hour-long drive back to Sara's apartment and headed out to lunch together -- Sara, Sara's Chinese friend Yannan, Kevin, and the other volunteers. There was some difficulty in finding a restaurant at first, as the area was (for a change) experiencing a power outage, and there was both no air conditioning and no quick way to make food in many of the local restaurants. Thankfully, though, we finally found a place, and dug into our rice and assorted family-style dishes with relish. (Many of the volunteers ordered two bottles of water, though Sara, Yannan, Kevin, and I held it steady at one).

After that, Kev and I bade the volunteers farewell and headed back into the city, and enjoyed

an interesting, if slightly sweaty, stroll through the Wudaokou Market, where we stayed until closing time at 7:30. I didn't buy anything except an ice cream, but Kevin found a few things he'd been looking to get before his return to the States. It was fun, but I couldn't help thinking how much more enjoyable the shopping would have been if I didn't feel kind of greasy all over from collected layers of sunscreen, sweat, dust, and grime. "Do you think we smell?" I whispered to Kevin at one point, as we pawed through racks of polo shirts in a smallish stall. "Probably," he muttered back, "but I bet it adds to our authenticity." Authenticity, indeed.

The Temple of Heaven and Wangfujing

I met up with Kevin bright and early Saturday morning, and we hopped on the now-familiar subway to Qianmen Zhan, a station right in the very heart of downtown Beijing, within walking distance of some of the city’s most exciting cultural and historical sites. After making our way through a tangle of alleyway markets (picking up, in the process, presents for my sister and mom, a gross iced tea, a yummy iced tea, some orange juice, and a little ceramic pot of yogurt which I drank with a straw) we finally found ourselves drawing close to our destination: Tian Tan, the Temple of Heaven. We strolled into a newly constructed, four-story mall-like complex half filled with vendor stalls, half empty space, but all mercifully air-conditioned (sadly, our real motivation in entering the building to begin with).

I acquired a cute green Adidas backpack to hold my purchases (one of which, Bean I bet you can guess which one this was,

and Mom, I can’t wait to give it to you, was rather heavy) and had a nice chat with the vendor. Kevin and I emerged once more into the blazingly white sun again and found a small stall at the side of the road selling baozi, steamed white buns filled with nearly every filling you could imagine (Kevin’s had meat in them, mine featured green beans and bai cai or white cabbage). We carried our bag of piping-hot baozi back into the mall complex, found a not-too-dirty spot on the stairs that was still relatively air-conditioned, and happily munched our lunch as we chatted about the temple we were about to visit.

The Temple of Heaven, or Tian Tan, was first built in 1420, and saw many important developments and additions during the Ming and Qing dynasties. Tian Tan was where the ancient emperors used to come to pray to the gods for good harvests and b

umper crops, through an elaborate ceremony of dressing, chanting, fasting, meditating, and preparing sacrifices to placate the gods. The shape of the park is unique and symbolic of this place's special role as a place where the holiest person in China (the emperor) came to commune with the gods and beg for abundance for his people. The northern wall is semi-circular, while the southern half of the park is rectangular, a pattern symbolic of the ancient belief that heaven is round and the earth square. As the emperor made his way from the southern part of the temple grounds to the northern extreme, he moved from the earthy realm of his people to become closer to the divinity whose aid he was trying to enlist. (Kevin and I did this exactly backwards, by the way, being the lao wai that we are, moving from north to south... oops).

The buildings of Tian Tan are arranged along this

north-south axis, with a large circular marble terrace in the south used to worship heaven at the winter solstice, linked with the northern temple used to pray in spring for a bountiful harvest by a 360-meter-long raised walk called the Danbi Bridge. The two altars and the bridge altogether compose an axis of more than 1200 meters long, flanked on either side by centuries-old cypress trees, formal walks, and other sacred buildings. For instance, to the inner south of the west celestial gate is the Fasting Palace, where feudal emperors observed abstention before their rituals of worship and prayer, while the western part of the outer temple is home to the Divine Music Administration, which we didn't see because it cost extra money to go in, but which apparently was used to teach and perform the ritual music accompanying the divine ceremonies.

Inside the northern temple itself, the sign at the entrance informed us, are such buildings as the Hall of Prayer for Good Harvests, the Hall of the Heavenly Emperor, the Imperial Vault of Heaven, the Beamless Hall, the Long Corridor, the Echo Wall, the Three Echo Stones, the Seven Star Stone and Nine-Dragon Juniper. It was truly a magical place. After an ice pop and the fourth iced-tea of the day (if I have any teeth left in my head by the end of this sugar-filled summer, it’s going to be a miracle), we finished up our tour of the park and temple grounds. Sadly, the Echo Wall was unavailable to visitors due to repairs, and Kevin and I wound up not quite being able to find the Fasting Palace, but besides these two, we saw nearly everything there was to see in the incredibly expansive grounds.

After all this walking, talking, and absorption of cultural and historical information, Kevin and I were about as wiped out as it is possible for two people to be. We dragged ourselves out the Western Gate and perched on a small, broilingly hot bit of concrete to plan the rest of our day. All I really wanted at this point in the day, I told Kevin plainly, was (1) to sit down, (2) to be cooled off. A taxi ride seemed the best way to provide both air conditioning and a softer, cooler place to sit than a hot, scratchy concrete slab, but this did not really solve the problem of where we ought to take the taxi to. We finally resolved to head to Wangfujing, one of the most popular spots in the city today, and gratefully climbed into the cool, cigarette-smelling interior of a nearby taxi

. The taxi driver laughed at us for going north to south instead of south to north, was astounded that we hadn't yet been to Wangfujing, and told us about a number of other Bejing hotspots we absolutely had to see before we left, even acting as a kind of tour guide as we cruised down the congested highway, pointing out a weather observatory and telling us a bunch of history about the building, which seemed to involve a kind of ancient Richter Scale based on frog statues holding balls in their mouths, which sounded really cool but was really a bit above my head in terms of Chinese listening comprehension. Kev thought it was cool, though.

Arriving at Wangfujing was like stepping into another universe, leaving behind the Beijing I've come to kn

ow and entering a wealthy, ultra-advanced, fully cosmopolitan city center. We meandered through a breathtakingly gorgeous hotel, stopped to use their (Western style!!) bathrooms (for me, this involved a mini-bath by the sink as I unsuccessfully attempted to remove a few layers of salt and dust from my person), and wandered about the premises gaping at the luxury that is so frequently nowhere to be found in China. I smiled graciously at the concierge and other uniformed hotel attendants, trying to look like I belonged there (“you’ve got instant authority,” Kevin informed me bluntly, “you’re white.”) despite my dusty legs, sweaty arms, and the damp backpack clinging to the back of my shirt. We found our way to a giant underground mall (Oriental Mall -- it has an above-ground element as well) filled with the kind of brands and goods that Chinese marketplaces provide cheap imitations of – Rolex, Burberry, Tiffany’s, Armani Exchange, the list goes on and on and on – and I suddenly became aware that, in addition to wanting to sit down again and be cooled off, I was powerfully hungry.

After a bunch of befuddled wandering and consultation of some truly useless mall directories,

we found the food area of the mall at last, and ordered a pair of ginormous, piping-hot bowls of ramen noodles at a Japanese place called Mian Ai Mian (which means something like “Face loves noodles” or “Noodles love face” or “Noodles love noodles” – it’s unclear as “mian” means a number of different things), where I proceeded to demolish the entire bowl, soup and all, before helping Kevin a bit with his dessert of strawberry ice cream decorated with tapioca balls and (inexplicably) cornflakes. [See picture for proof of this feat – note Kevin’s not-emptied bowl in the background.]

More than a little full after all that ramen, but feeling refreshed and ready for new adventures, we made our way back to the surface and emerged into Wangfujing. Created to lead to a well drilled near the Yuan Dynasty Prince's Mansion nearly 700 years ago, the street of Wangfujing is now one of China's most popular shopping districts. Legend has it that an emperor during the Ming Dynasty wanted all of his 10 brothers to

build their mansions along this street in order to make it easy for him to keep an eye on them and make sure they didn't amass too much political power. The street was therefore christened "

Shi wang fu" (Ten Princes' Mansions), merged with the old purpose of the street to the current-day name of "

Wang fu jing" ("

jing" means well). Kev and I actually saw the well, which has been symbolically restored and has a little fence around it off one of the small alleyways. Kevin and I sampled some of the local delicacies (him: sugared grapes on a stick, me: coconut juice straight out of the coconut) and steered clear of some of the others (scorpions, seahorses, pupae, crickets, and whole baby birds on a stick, to give just a few examples) as we strolled about taking in the sights and marvelling at the almost surreal cleanliness of the alleyway marketplace, so different from more authentic shopping opportunities in the dirty alleys of the rest of Beijing.

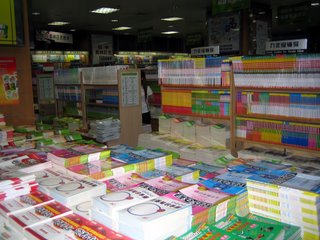

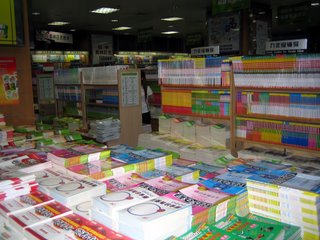

On our way back up the street, we made a stop at the Xinhua Book Store, which is apparently the

biggest bookstore in all of China. During our first trip past, I had refrained from entering, knowing that I would probably wind up spending the rest of the evening in the store and didn’t want to take Kevin away from his sight-seeing, but as he wanted to go in on our way back, I was certainly not going to complain. Kevin bought

The Art of War and

The Communist Manifesto, and I purchased

Tao Te Ching (The Book of Changes),

The Analects, The Life and Wisdom of Confucius, Tracing the Roots of Chinese Characters: 500 Cases, and an amazing book published by Yale University Press, but mercifully not as expensive as all the other imported books they had for sale (I purchased only Chinese books, as the English ones were all still American/European prices), called

Key Concepts in Chinese Philosophy. Although this shopping spree compromises one of my larger purchases in China (and yes, it does figure that it was in a bookstore... is anyone surprised?

anyone? anyone? Bueller...?), all together these books cost less than $20 USD. Simply unbelievable.

It was also in Wangfujing that I experienced two of my Chinese "firsts," each of which says loads about the current status of (and flaws in) Chinese society today, because they are "firsts" here but perfectly common occurances back home: I saw the first pregnant woman ever, in all my weeks in China, and caught sight of the first wheelchair-bound Chinese person. Each of these bears very interestingly on a different aspect of China's societal and governmental policies, and both are linked to the omnipresent, all-pervasive population problem, but I won't get too into it here for, erm, fairly obvious reasons, which might or might not have to do with internet censorship. That's all I'm sayin.